Very Important read for all parents with young children

MALCOLM GLADWELL GOT US WRONG: OUR RESEARCH WAS KEY TO THE 10000-HOUR RULE, BUT HERE’S WHAT GOT OVERSIMPLIFIED

Malcolm Gladwell (Credit: Hachette Book Group)

Yes, it takes effort to be an expert. But Gladwell based 10,000-hour rule in part on our work, and misunderstood

ANDERS ERICSSON AND ROBERT POOL

Adapted from “Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise“

In 1993 one of us (Anders Ericsson) published the results of a study on a group of violin students in a music academy in Berlin that found that the most accomplished of those students had put in an average of ten thousand hours of practice by the time they were twenty years old. That paper, written with co-authors Ralf Krampe and Clemens Tesch-Römer, would go on to become a major part of the scientific literature on expert performers, but it was not until 2008, with the publication of Malcolm Gladwell’s “Outliers,” that the paper’s results attracted much attention from outside the scientific community. In his discussion of what it takes to become a top performer in a given field, Gladwell offered a catchy phrase: “the ten-thousand-hour rule.” According to this rule, it takes ten thousand hours of practice to become a master in most fields. As evidence, Gladwell pointed to our results on the student violinists, and, in addition, he estimated that the Beatles had put in about ten thousand hours of practice while playing in Hamburg in the early 1960s and that Bill Gates put in roughly ten thousand hours of programming to develop his skills to a degree that allowed him to found and develop Microsoft. In general, Gladwell suggested, the same thing is true in essentially every field of human endeavor — people don’t become expert at something until they’ve put in about ten thousand hours of practice.

The rule is irresistibly appealing. It’s easy to remember, for one thing. It would’ve been far less effective if those violinists had put in, say, eleven thousand hours of practice by the time they were twenty. And it satisfies the human desire to discover a simple cause-and-effect relationship: just put in ten thousand hours of practice at anything, and you will become a master.

Unfortunately, this rule — which is the only thing that many people today know about the effects of practice — is wrong in several ways. (It is also correct in one important way, which we will get to shortly.) First, there is nothing special or magical about ten thousand hours. Gladwell could just as easily have mentioned the average amount of time the best violin students had practiced by the time they were eighteen — approximately seventy-four hundred hours — but he chose to refer to the total practice time they had accumulated by the time they were twenty, because it was a nice round number. And, either way, at eighteen or twenty, these students were nowhere near masters of the violin. They were very good, promising students who were likely headed to the top of their field, but they still had a long way to go when at the time of the study. Pianists who win international piano competitions tend to do so when they’re around thirty years old, and thus they’ve probably put in about twenty thousand to twenty-five thousand hours of practice by then; ten thousand hours is only halfway down that path.

And the number varies from field to field. Steve Faloon, the subject of an early experiment on improving memory, became better at memorizing strings of digits than any other person in history after only about two hundred hours of practice. Now, thirty years later, with improved training techniques the world’s best digit memorizers can recall strings of digits that are several times longer than Steve Faloon’s best. We don’t know exactly how many hours of practice these top performers have put in, but it is likely well under ten thousand.

Second, the number of ten thousand hours at age twenty for the best violinists was only an average. Half of the ten violinists in that group hadn’t actually accumulated ten thousand hours at that age. Gladwell misunderstood this fact and incorrectly claimed that all the violinists in that group had accumulated over ten thousand hours.

Third, Gladwell didn’t distinguish between the type of practice that the musicians in our study did — a very specific sort of practice referred to as “deliberate practice” which involves constantly pushing oneself beyond one’s comfort zone, following training activities designed by an expert to develop specific abilities, and using feedback to identify weaknesses and work on them — and any sort of activity that might be labeled “practice.” For example, one of Gladwell’s key examples of the ten-thousand-hour rule was the Beatles’ exhausting schedule of performances in Hamburg between 1960 and 1964. According to Gladwell, they played some twelve hundred times, each performance lasting as much as eight hours, which would have summed up to nearly ten thousand hours. “Tune In,” an exhaustive 2013 biography of the Beatles by Mark Lewisohn, calls this estimate into question and, after an extensive analysis, suggests that a more accurate total number is about eleven hundred hours of playing. So the Beatles became worldwide successes with far less than ten thousand hours of practice. More importantly, however, performing isn’t the same thing as practice. Yes, the Beatles almost certainly improved as a band after their many hours of playing in Hamburg, particularly because they tended to play the same songs night after night, which gave them the opportunity to get feedback — both from the crowd and themselves — on their performance and find ways to improve it. But an hour of playing in front of a crowd, where the focus is on delivering the best possible performance at the time, is not the same as an hour of focused, goal-driven practice that is designed to address certain weaknesses and make certain improvements — the sort of practice that was the key factor in explaining the abilities of the Berlin student violinists.

A closely related issue is that, as Lewisohn argues, the success of the Beatles was not due to how well they performed other people’s music but rather to their songwriting and creation of their own new music. Thus, if we are to explain the Beatles’ success in terms of practice, we need to identify the activities that allowed John Lennon and Paul McCartney—the group’s two primary songwriters—to develop and improve their skill at writing songs. All of the hours that the Beatles spent playing concerts in Hamburg would have done little, if anything, to help Lennon and McCartney become better songwriters, so we need to look elsewhere to explain the Beatles’ success.

This distinction between deliberate practice aimed at a particular goal and generic practice is crucial because not every type of practice leads to the improved ability that we saw in the music students or the ballet dancers. Generally speaking, deliberate practice and related types of practice that are designed to achieve a certain goal consist of individualized training activities — usually done alone — that are devised specifically to improve particular aspects of performance.

The final problem with the ten-thousand-hour rule is that, although Gladwell himself didn’t say this, many people have interpreted it as a promise that almost anyone can become an expert in a given field by putting in ten thousand hours of practice. But nothing in the study of the Berlin violinists implied this. To show a result like this, it would have been necessary to put a collection of randomly chosen people through ten thousand hours of deliberate practice on the violin and then see how they turned out. All that the Berlin study had shown was that among the students who had become good enough to be admitted to the Berlin music academy, the best students had put in, on average, significantly more hours of solitary practice than the better students, and the better and best students had put in more solitary practice than the music-education students.

The question of whether anyone can become an expert performer in a given field by taking part in enough designed practice is still open, and we offer some thoughts on that issue elsewhere. But there was nothing in the original study to suggest that it was so.

Gladwell did get one thing right, and it is worth repeating because it’s crucial: becoming accomplished in any field in which there is a well-established history of people working to become experts requires a tremendous amount of effort exerted over many years. It may not require exactly ten thousand hours, but it will take a lot.

Research has shown this to be true in field after field. It generally takes about ten years of intense study to become a chess grandmaster. Authors and poets have usually been writing for more than a decade before they produce their best work, and it is generally a decade or more between a scientist’s first publication and his or her most important publication — and this is in addition to the years of study before that first published research. A study of musical composers by the psychologist John R. Hayes found that it takes an average of twenty years from the time a person starts studying music until he or she composes a truly excellent piece of music, and it is generally never less than ten years. Gladwell’s ten-thousand-hour rule captures this fundamental truth — that in many areas of human endeavor it takes many, many years of practice to become one of the best in the world — in a forceful, memorable way, and that’s a good thing.

On the other hand, emphasizing what it takes to become one of the best in the world in such competitive fields as music, chess, or academic research leads us to overlook what we believe to be the more important lesson from the study of the violin students. When someone says that it takes ten thousand — or however many — hours to become really good at something, it puts the focus on the daunting nature of the task. While some may take this as a challenge — as if to say, “All I have to do is spend ten thousand hours working on this, and I’ll be one of the best in the world!”—many will see it as a stop sign: “Why should I even try if it’s going to take me ten thousand hours to get really good?” As Dogbert observed in one “Dilbert” comic strip, “I would think a willingness to practice the same thing for ten thousand hours is a mental disorder.”

But we see the core message as something else altogether: In pretty much any area of human endeavor, people have a tremendous capacity to improve their performance, as long as they train in the right way. If you practice something for a few hundred hours, you will almost certainly see great improvement — it took Steve Faloon only a couple of hundred hours of practice to become the best ever at memorizing strings of digits — but you have only scratched the surface. You can keep going and going and going, getting better and better and better. How much you improve is up to you.

This puts the ten-thousand-hour rule in a completely different light: The reason that you must put in ten thousand or more hours of practice to become one of the world’s best violinists or chess players or golfers is that the people you are being compared to or competing with have themselves put in ten thousand or more hours of practice. There is no point at which performance maxes out and additional practice does not lead to further improvement. So, yes, if you wish to become one of the best in the world in one of these highly competitive fields, you will need to put in thousands and thousands of hours of hard, focused work just to have a chance of equaling all of those others who have chosen to put in the same sort of work.

One way to think about this is simply as a reflection of the fact that, to date, we have found no limitations to the improvements that can be made with particular types of practice. As training techniques are improved and new heights of achievement are discovered, people in every area of human endeavor are constantly finding ways to get better, to raise the bar on what was thought to be possible, and there is no sign that this will stop. The horizons of human potential are expanding with each new generation.

Adapted from “Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise” by Anders Ericsson and Robert Pool. Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Copyright © 2016 by K. Anders Ericsson and Robert Pool. Reprinted with permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.

This article was originally posted on SALON’s page

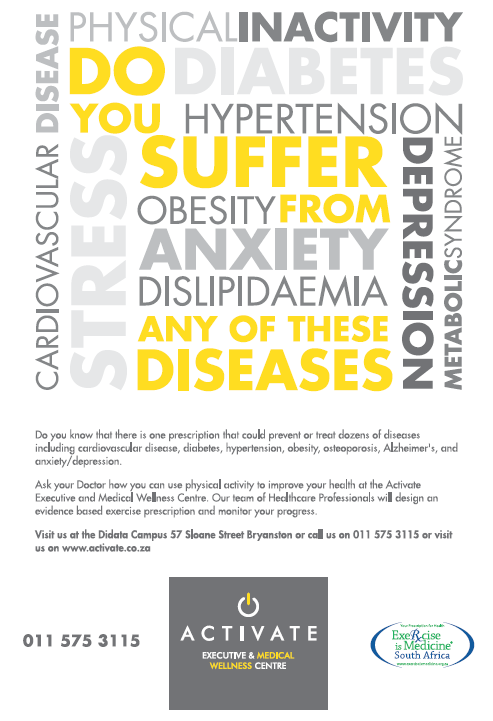

HIIT Training or “High Intensity Interval Training” is all the hype at the moment and is easily among the top fitness trends for 2015-2016. Have you ever wondered why it is so effective at helping you reach your goals, whether that be weight loss or increasing your cardiovascular fitness?

HIIT Training or “High Intensity Interval Training” is all the hype at the moment and is easily among the top fitness trends for 2015-2016. Have you ever wondered why it is so effective at helping you reach your goals, whether that be weight loss or increasing your cardiovascular fitness?